In Europe, dependence on GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems), satellite navigation systems such as the U.S. GPS or Europe’s Galileo, is no longer just an engineering concern. It has become a tangible risk for aircraft, ships, and the energy and telecom networks that rely on ultra-precise timing.

In recent years, reports of interference have mounted: disrupted signals, complicated flight paths, and ship tracks that “jump” across navigation displays. In October 2025, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) formally condemned these practices, singling out jamming and spoofing widely attributed to Russia. For ICAO, they directly undermine aviation safety and violate the Chicago Convention, the foundational treaty of international civil aviation.

At the same time, the European Union is moving quickly on another front: cybersecurity. With the Cyber Solidarity Act, Brussels is standing up a network of interconnected cyber-monitoring centers,the European Cyber Shield, and a reserve of cyber specialists that can be deployed in a crisis. The objective is clear: detect attacks earlier, share alerts faster, and give operators real Plan B options to keep flying, sailing, and operating even when GNSS (GPS, Galileo, etc.) goes dark.

When a commercial route stops because of GNSS

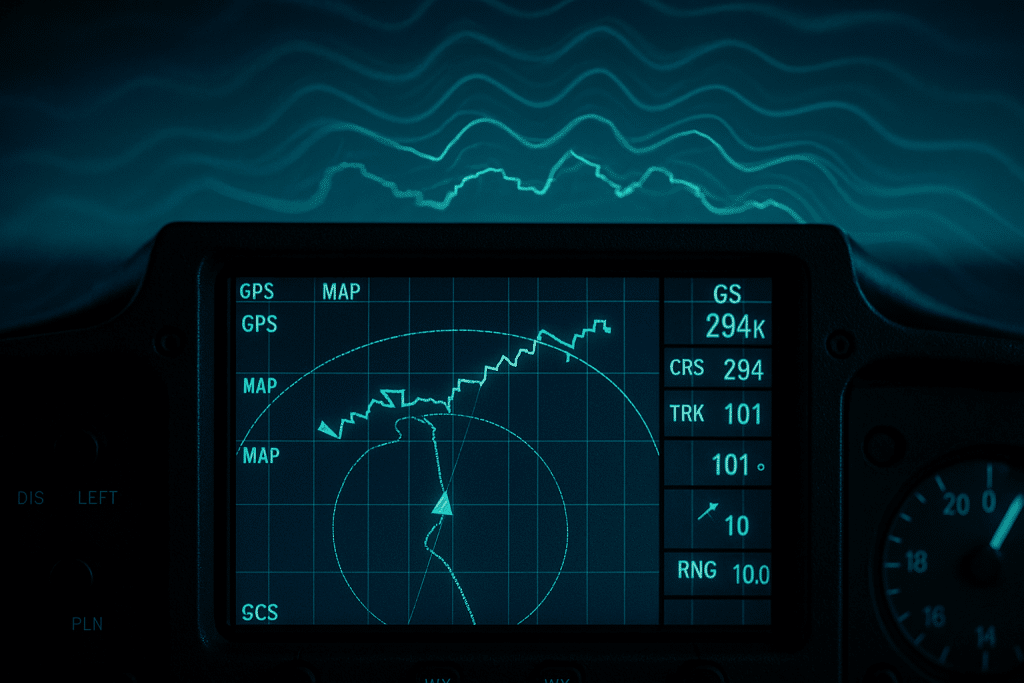

Civil aviation has already had a taste of this “uncertain GNSS” environment.

In April 2024, Finnair suspended flights to Tartu, Estonia, for a month. The trigger was GPS interference during approach, the most sensitive phase of a flight. The workaround was to introduce an approach procedure that no longer relied on satellite signals, but on traditional ground-based radio aids.

For aircrews and regulators, the episode was a wake-up call: having procedures and tools that do not depend on GNSS is no longer a doctrinal luxury, but an essential safety net.

Cyber exercises now pull in sky and space

On the cyber defense side, major European exercises have evolved accordingly.

The Locked Shields and Crossed Swords exercises, run under NATO and European partner auspices, have progressively integrated new scenarios, including:

- attacks on power and telecom networks,

- disruption of satellite links,

- exploitation or protection of 5G networks,

- controlled use of countermeasures in cyberspace.

Another notable shift is the growing presence of civilian and private-sector actors within the staffs that take part in these drills. That reflects a simple reality: crises are no longer purely military; they are hybrid by design. The boundary between aviation safety, cybersecurity, and the protection of critical infrastructure is increasingly porous.

Continuity as the red thread

In aviation, the equation is simple but demanding:

keep aircraft taking off and landing safely even when the GNSS environment is compromised.

That requires:

- crews who still know how to fly using ground-based radio aids and the associated procedures,

- control towers equipped with sensors able to spot signal anomalies,

- clear Notices to Air Missions (NOTAMs) and rapid rerouting plans.

For drones, the logic is similar:

- multiply navigation sources (GNSS, inertial, vision, and potentially backup signals from LEO satellites or eLoran),

- test “loss of GNSS” procedures in realistic conditions to keep trajectories safe and avoid endangering other aircraft.

For ground-based air defense, the core issue is time synchronization between radars, command centers, and firing units. Forces need resilient clocks and hardened synchronization protocols that can keep working even when the reference GNSS signal is jammed.

At sea, automated spoofing alarms on the bridge – and a return to good seamanship, cross-checking the GNSS fix with coastal radar, inertial data, or simple visual bearings, are once again becoming central practices.

How to tell if Europe has really stepped up

Three indicators will show whether Europe has truly moved up a gear:

- The number of OSNMA-capable receivers able to authenticate Galileo signals and the measured impact on GNSS spoofing attempts.

- The speed and quality of alerts produced by the European Cyber Shield: reaction time, maps of interference zones, and guidance pushed to operators.

- Progress on backup programs (LEO-based navigation, eLoran): costs, integration into existing systems, and operational doctrine.

If these three strands advance together – more secure satellites, deployed Plan Bs, and an effective warning chain – Europe will finally field a multilayer positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) architecture, built around but also beyond GNSS. In practice, that means a system able to absorb attacks without bringing aviation or maritime traffic to a halt.