Spain’s Air and Space Force is entering a decisive phase. Its aging F/A-18 Hornets are nearing retirement just as the Spanish–German–French Future Combat Air System (FCAS) will not enter service before 2040. Balancing industrial continuity, operational requirements, and geopolitical choices, Madrid faces a critical question: which fighter will guarantee Spanish air superiority over the next fifteen years?

Several paths are on the table: extend the Eurofighter line, consider Turkey’s KAAN, or wait for FCAS. Each option reflects a different vision of the role Spain intends to play in European defense.

The solid baseline: Eurofighter “Halcón II”

The only officially committed path is the Eurofighter Halcón II program—a 2024 order for 25 new aircraft, with deliveries phased between 2030 and 2035.

This choice sustains Spain’s aerospace industrial base (Airbus Defence in Getafe and CASA), while reinforcing NATO standardization and preserving national know-how in maintenance and training.

Despite its upgrades (Captor-E AESA radar, enhanced electronic warfare, strengthened datalinks), the Eurofighter remains a “4.5-generation” platform: a capable, multirole, highly digital aircraft, but non-stealthy, with data fusion and automation still short of emerging benchmarks. That is precisely where Spain’s debate begins: the technological leap to fifth generation.

What “fifth-generation fighter” really means

Fifth generation represents a break in how air combat is conceived. It is not just radar stealth; it is an integrated ecosystem of sensors, connectivity, and data processing.

Typically, a fifth-generation aircraft combines:

- Multispectral stealth (low observable): shaping and materials to reduce radar, infrared, and acoustic signatures.

- Real-time data fusion: the pilot (or onboard AI) sees a unified tactical picture from multiple on- and off-board sensors.

- Network-centric operations: the jet does not fight alone; it continuously exchanges with other platforms (aircraft, drones, ground-based air defenses) within a “combat cloud.”

- New-generation sensors: multi-band AESA radar, IRST, and tightly integrated active electronic warfare.

- AI-assisted mission systems: automated threat detection, target prioritization, and teaming with “loyal wingman” drones.

- Predictive maintenance and open architectures: frequent software updates and modular upgrades.

The U.S. F-35 is the current operational reference. Other, South Korea’s KF-21, Turkey’s KAAN, and Japan’s FX, aim to approach that standard, each with its own level of industrial autonomy. This is the segment Spain seeks to bridge: acquiring a “5G-like” interim capability before FCAS.

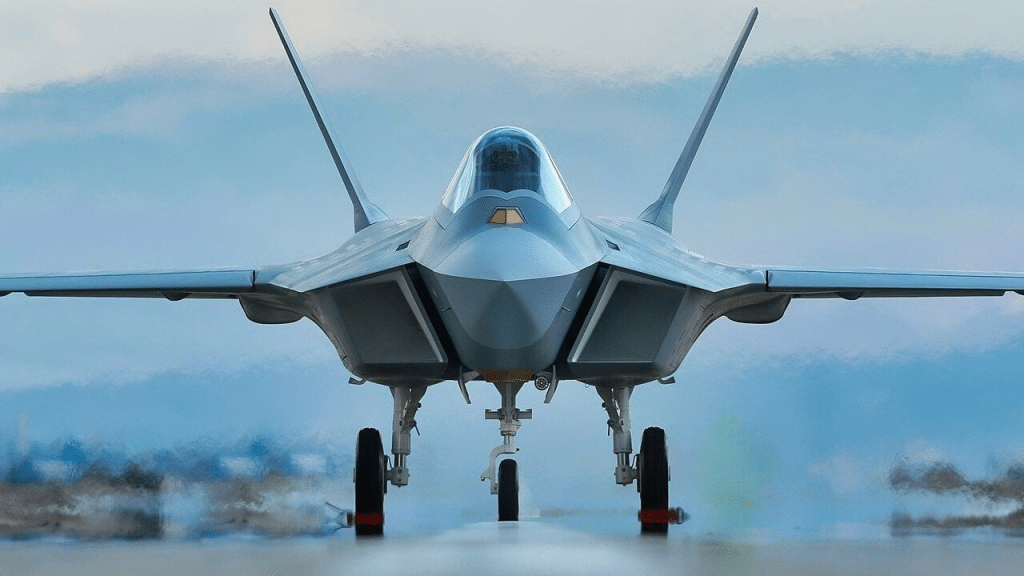

The Turkish bet: KAAN as a transition option

In that window, Turkey’s KAAN has emerged as a point of interest. Developed by Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI), it promises a stealth-forward design, an indigenous AESA radar, internal weapons bays, and modular avionics with AI-enabled functions.

Sources close to Spain’s Ministry of Defense indicate Madrid is watching the program closely, without committing. The idea would be to assess KAAN as an interim or complementary option to the Typhoon should FCAS timelines slip.

The appeal is not purely technological. Spain already cooperates with Ankara on advanced training via the Hürjet, selected to replace the F-5 trainer fleet. Government decision of 24 September 2025 to order 45 Hürjets,with first deliveries from 2028 and some industrial integration in Spain. This bridge could, in time, open the door to deeper cooperation on KAAN.

“KAAN attracts Madrid because it offers a higher degree of autonomy and technology transfer than a U.S. purchase,” notes The Defense Post. “But it is still, essentially, a bet on a prototype.”

Questions remain over software maturity, NATO compatibility (Link-16, IFF Mode 5), cost of ownership, and real-world availability. Until those are validated, KAAN is more promise than capability.

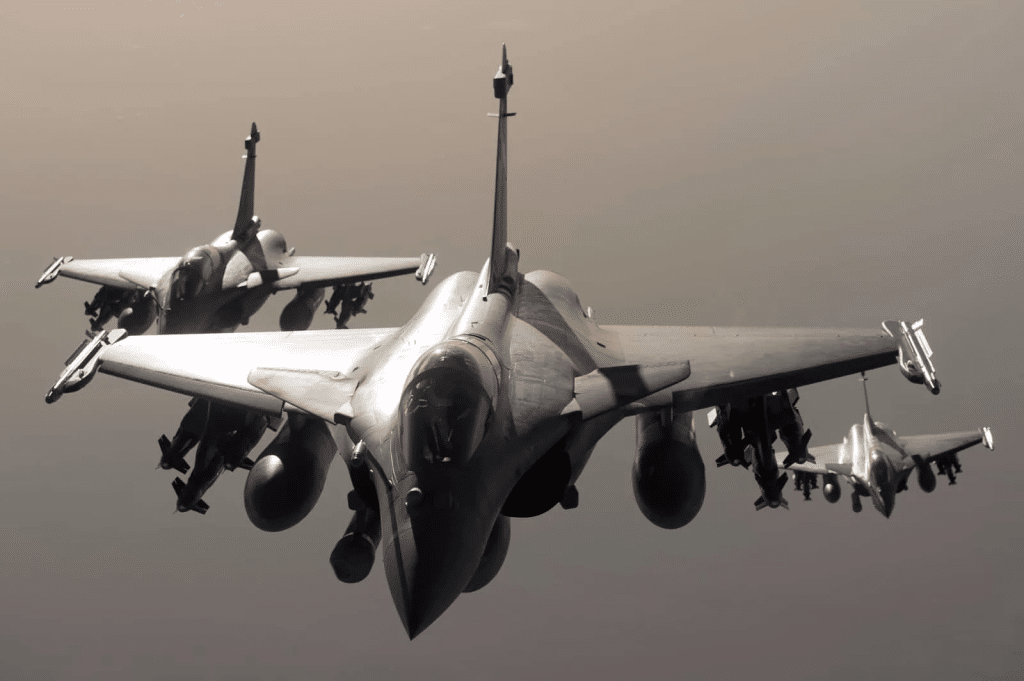

The French Rafale: credible, but secondary

France’s Rafale F4/F5 remains a credible fallback. It is robust, interoperable, and combat-proven, with advanced electronic-warfare and connectivity—yet it is not stealthy.

The main brake is industrial: most value would accrue to Dassault and Safran rather than Airbus Spain. Madrid has just injected €3.68 billion into a multi-platform acquisition package with industrial-loan components (Hürjet, C295, helicopters, etc.). In that context, a French purchase is harder to justify.

FCAS: strategic patience

In the background, Spain remains firmly committed to FCAS with Germany and France. Conceived as a system set, it will integrate a sixth-generation fighter, combat drones, and a combat cloud linking sensors and effectors. Indra and Airbus España are deeply involved in sensors, electronic warfare, and mission-data management.

However, with a first flight expected around the mid-2030s and full operational capability after 2040, FCAS demands long-term investment—and a realistic transition strategy.

Spain’s next fighter is not just about specifications; it is about strategic intent. Madrid seeks to preserve technological autonomy while ensuring fleet coherence and the stability of its aerospace industry. Eurofighter secures the present, FCAS defines the horizon, and KAAN is the bold card that—if it matures—could help Spain join the small club able to field a true fifth-generation fighter: stealthy, connected, intelligent, and collaborative. The next decade will tell whether that bet pays off.